Oregon’s Child Care Industry

June 22, 2023Many working parents in Oregon rely on the child care industry for safe, affordable, and educational care for their children. Among parents of young children under the age of six, nine out of 10 fathers and two-thirds of mothers are working. Parents of children under six years of age make up 12% of Oregon’s workforce, and those with children ages six to 17 make up another 19%. Oregon employers benefit from the services of child care providers because these services help their workforce continue to be stable, reliable, and productive.

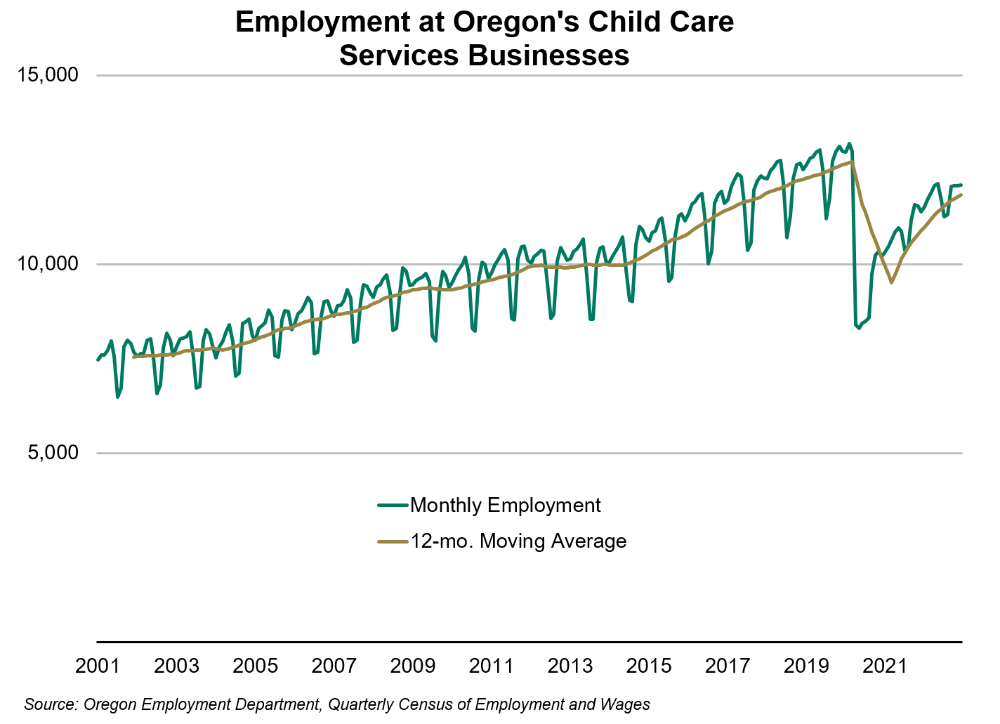

The Pandemic Recession highlighted the importance of the industry, as child care businesses faced new restrictions and risks of providing care in Oregon communities. Employment in child day care services dropped a staggering 35% in one month between March and April 2020, and the industry has yet to regain all of those job losses. Child care businesses regained 81% of the April 2020 job losses by December 2022.

Job growth was strong across the economy in 2021 and 2022, and the number of job openings outpaced available labor supply. Many employers have reported significant difficulty filling their open positions, including child care centers. Employers responding to the Oregon Job Vacancy Survey reported 72% of job openings as difficult to fill in 2021 and 2022. Employers reported 75% of their vacancies for childcare workers in 2022 were difficult to fill, along with 55% of openings for preschool teachers.

The supply of child care has improved for preschool age children since prior to the pandemic in early 2020. Still, as of December 2022, almost all Oregon counties are considered child care deserts for infants and toddlers, while half of counties remain child care deserts for preschoolers. Improvement in the number of preschooler child care slots has been driven by targeted, and partially pandemic-related, public investments in growing the capacity of the child care sector in the state.

Child Care Businesses Still Recovering After the Pandemic

The child care sector was hard hit at the onset of the Pandemic Recession and heavily affected by the restrictions put in place to stop the spread of COVID-19. Due to the nature of such a close-contact business as caring for children, and to the many changes we all dealt with in 2020 that suddenly shifted both demand for and supply of child care, employers had to shift rapidly to reopen with new safety precautions and limitations to group sizes, cohorts, and a new, much smaller, staffing footprint.

At the onset of COVID-19, the private-sector child care industry employed about 13,000 jobs in March 2020. It swiftly dropped to 8,400 jobs in April 2020. As of December 2022, the most recent month of available data, Oregon’s child care businesses had regained 3,700 of the jobs lost in spring 2020, reaching about 12,100 jobs.

While the child care sector lost a lot of jobs, some temporarily and some permanently, almost all child care businesses survived the pandemic. In first quarter 2020, child care businesses numbered 1,427 and one quarter later the sector dropped to a low of 1,377 businesses – a very small decrease compared with the loss in jobs. As of fourth quarter 2022 the count had reached 1,494.

Over the long-term, child care has seen strong growth. Since the industry has a reliable seasonal pattern, with a drop in jobs during each summer, the 12-month moving average is included in the graph to make the overall trend a bit easier to follow. From 2002 to 2022, Oregon’s child care businesses grew 55%; just about as strong as the 68% growth in private-sector health care and social assistance, the broader sector of which child day care services is a small part. Total private-sector employment grew 27% between 2002 and 2022.

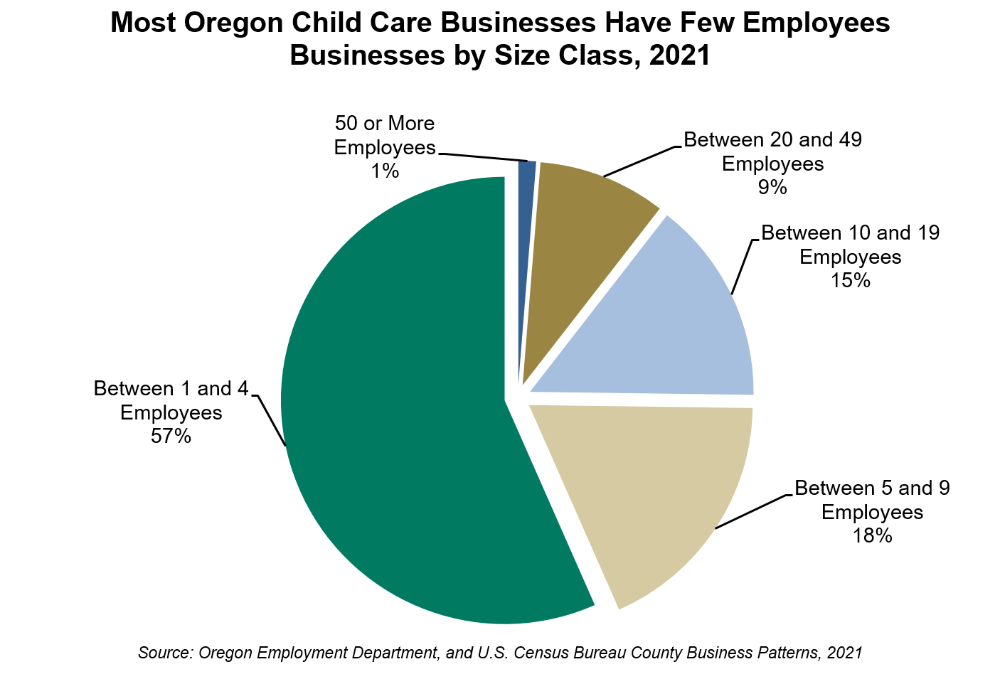

Child care businesses tend to be small operations. In 2021, more than half of Oregon’s child care businesses had four or fewer employees. Just 10% of child care businesses employed 20 or more workers.

Average wages are low in the industry, but increased significantly in 2022, rising above $30,000 per year on average for the first time amid high inflation, an increasing minimum wage, and stiff competition for workers to fill record levels of job openings across the economy. Total payroll of child care businesses with employees in 2022 shot up 18% over the year to $385 million. That’s 28% above the sector’s total payroll of $301 million in 2019. This averages out to almost $32,600 per worker, up from $23,900 prior to the pandemic in 2019.

While well above pre-pandemic wages, the child care average is about half the private-sector average of $65,400. The low average wage is due to the low wages of the occupations that dominate the industry. For example, the median wage of a preschool teacher in Oregon in 2022 was $17.58 per hour, and the median wage for childcare workers was $15.28. These two occupations account for almost two-thirds of the employment in the child care industry.

Not Enough Child Care Supply

Child care supply, especially for infants through age two, is too scarce across most of the state. The Oregon Child Care Research Partnership report Oregon’s Child Care Deserts: 2022 found that for the youngest children, infants through age two, 35 out of Oregon’s 36 counties remained in child care desert status as of December 2022. In early 2020, prior to the pandemic, all 36 counties were considered to be child care deserts – defined as an area with less than one child care slot per three children of a given age group. Gilliam County dropped out of child care desert status for the youngest children in the 2022 analysis, and as it is one of Oregon’s smaller counties, the numerical changes were quite small, with the number of child care slots increasing slightly and the number of infants and toddlers decreasing slightly.

Twelve Oregon counties are considered severe deserts for infants and toddlers, with at most one child care slot per 10 children from birth to two years old. Almost all of them are nonmetro counties. In order of severity, counties with the least access to child care for infants and toddlers are: Lake, Curry, Harney, Grant, Tillamook, Linn, Clatsop, Crook, Lincoln, Douglas, Union, and Wheeler.

Child care supply for preschool age children has improved in much of the state since early 2020, prior to the pandemic. In 2018, 27 counties were child care deserts for families with preschoolers. By 2020 that dropped to 25 counties, and in recovery from the pandemic it’s down to 18 counties in December 2022. No Oregon counties are considered severe deserts for the preschool age group.

Increased Access Driven by Public Funding

Public funding for child care has improved access recently. Without public funding, all but three counties (Multnomah, Deschutes, and Washington) would have been child care deserts for families with preschoolers as of December 2022. In the Oregon’s Child Care Deserts: 2022 report, publicly funded slots include slots funded by Oregon Prenatal to Kindergarten (Head Start Prekindergarten and Early Head Start), Preschool Promise, Baby Promise, Federal and Tribal Head Start/Early Head Start, and Federal Migrant and Seasonal Head Start managed by the Oregon Child Development Coalition.

Almost one out of three regulated child care slots for preschoolers in Oregon was publicly funded in December 2022 (31%). A much smaller share of infant and toddler slots was publicly funded (11%), but targeted investments are making a difference in supply for both age groups. The number of publicly funded slots for infants and toddlers grew 49% with increased state funding since the last report in early 2020, while the number of public preschooler slots increased 30%.

These investments are absolutely crucial to a functioning child care system in rural areas. As stated in the report, “Public funding is typically directed to areas where conditions for market care are weak. These targeted areas are in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties, but they make up a greater percentage of the slots in nonmetropolitan counties where the conditions to support market care are especially weak and thus the number of market slots is small.” In Oregon’s nonmetro counties, publicly funded child care slots made up 33% of supply for care of infants and toddlers, and 58% of child care slots for preschoolers. In metro counties, the public component accounted for 8% of infant and toddler slots and 25% of preschooler slots.

The child care industry has grown over the long-term in response to the increasing numbers of families in which both parents work, and to the increasing number of households headed by women. Public investments in early childhood learning are making a difference in the supply of child care, but almost all Oregon counties remain child care deserts for the youngest children, and half are deserts for preschoolers as well. Efforts to improve pay, professional development, and working conditions as well as supply will help to retain and recruit the early learning workforce of the future. The need for child care services isn’t going anywhere. Families and businesses rely on a stable child care industry.