Head Out on the Highway: Baker County Commuter Data - 2019

December 29, 2021 The thought of commuting to work may conjure images of the Westside’s urban sprawl and life in the big city. However, living in one town and working in another is common among Oregon’s rural workforce as well. The U.S. Census Bureau provides data on workforce commute patterns with its On-The-Map tool. The most recent data reveals that 27% of Baker County’s workforce came from outside the county in 2019 while 36% of workers living in Baker commuted to jobs in a different county.It’s common for workers to commute to or from neighboring counties. In 2019, 37.1% of Baker County’s inbound commuters came from the four Oregon counties that make up its border. Union County held the top spot, shipping 22.9% of all inbound commuters. Union County supplied 6.1% of Baker’s total workforce (the largest group from La Grande). Malheur County supplied 2.3% of Baker’s workforce (the largest group from Ontario). Grant and Wallowa counties supplied 0.8% and 0.7% of the workforce, respectively.

The four neighboring counties served as the destination for 31.4% of Baker’s outbound commuters. Union held the top spot here as well receiving 20.8% of all outbound commuters. For workers who reside in Baker County, Union County supplied 7.4% of jobs (the majority in La Grande). Malheur County supplied 2.0% of jobs (the largest group in Ontario). Grant and Wallowa counties supplied 1.0% and 0.7% of jobs, respectively.

The majority of Baker County commuters lived or worked beyond the four neighboring counties in 2019. Roughly three-fourths of Baker commuters, however, still lived and worked in Oregon. Umatilla and Deschutes counties were high on the list of where Baker commuters lived. Umatilla and Multnomah counties were high on the list of where commuters worked. The majority of commuters outside of Oregon were tied to Idaho and Washington. Payette and Washington counties, in Idaho, were high on the list of where workers lived. Payette borders Malheur County and offers quick access to Interstate 84. Washington County runs along Baker’s border on the opposite side of the Snake River and also offers quick access to Interstate 84 just south of Farewell Bend. Benton County, Washington, home to Richland and Kennewick (two components of the Tri-Cities) was high on the list for where Baker commuters worked. Franklin County, Washington, home to Pasco (the third component of the Tri-Cities) was also high on the list. Idaho shipped 17.7% of Baker County commuters while receiving 6.6%. Washington shipped just 1.7% of Baker County commuters while receiving 13.7%.

The majority of Baker County commuters lived or worked beyond the four neighboring counties in 2019. Roughly three-fourths of Baker commuters, however, still lived and worked in Oregon. Umatilla and Deschutes counties were high on the list of where Baker commuters lived. Umatilla and Multnomah counties were high on the list of where commuters worked. The majority of commuters outside of Oregon were tied to Idaho and Washington. Payette and Washington counties, in Idaho, were high on the list of where workers lived. Payette borders Malheur County and offers quick access to Interstate 84. Washington County runs along Baker’s border on the opposite side of the Snake River and also offers quick access to Interstate 84 just south of Farewell Bend. Benton County, Washington, home to Richland and Kennewick (two components of the Tri-Cities) was high on the list for where Baker commuters worked. Franklin County, Washington, home to Pasco (the third component of the Tri-Cities) was also high on the list. Idaho shipped 17.7% of Baker County commuters while receiving 6.6%. Washington shipped just 1.7% of Baker County commuters while receiving 13.7%.It may be difficult to imagine commuting more than one or two hours for work. For perspective, a Boise to Baker City commute or a Hermiston to Baker City commute takes more than two hours. However, commuting is not limited to the arduous daily drive. While On-The-Map commute data doesn’t tell us how commutes occurred or how long commuters stayed for work, several scenarios are possible and likely. Commuters can be full or partial telecommuters, working for a firm outside their county of residence and infrequently making a physical commute. Home based call center employees and outside sales representatives are examples of occupations that fit this scenario. Commuters can commute for extended shifts, short stays, or even seasons, traveling to where the job demand is and returning home when the work is complete. Nurses and physicians are examples of extended shift or short stay occupations. Commuters with either of these occupations could work for a two or three day shift and then return home for three or four days. Construction workers on special projects and certain agriculture workers are examples of seasonal positions that require extended stays, but might not encourage year round residence.

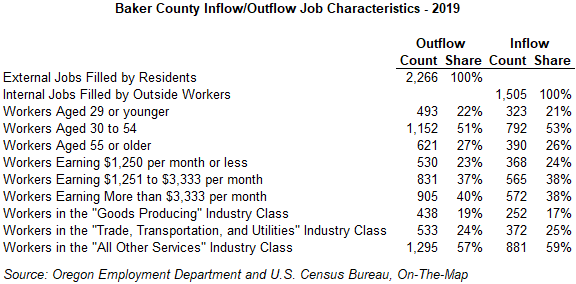

The accompanying table provides some additional points of interest. Baker County exports more workers than the county imports. The largest share of commuters leaving the county earned more than $3,333 a month, but this was a tight race with those making $1,250 to $3,333 a month. The share of commuters entering the county was nearly equal for each of these two wage categories. In addition, the largest share of commuters in either direction were 30 to 54 years old. On-The-Map can provide details not contained in this report or the table, so check out the data tool or drop me a line if you have any questions.